Invisible Spaces of Parenthood

“Is it possible at this stage to posit that parenthood is invisible because women are? Whether we like to admit it or not it is very much still ‘women and children’ and, in a way, the invisibility of women. From here on, it is the usual feminist rant. However, it might be important to acknowledge that parenthood’s invisibility is an indicator of something else.”

— Lamis Bayar

Andrea Francke, a London based artist and mother, opened a functioning daycare center (crèche) for her graduate show. Francke, who moved to Britain from Brazil to study, assumed that having a child would be just a matter of adopting some new routines and then back to business as usual with her art work, social life, etc. When the Chelsea College of Art and Design decided to close the nursery where Francke kept her son while she attended classes, the artist realized that daily life with a child would not be going along as planned.

Francke joined with other parents to protest the nursery closing but the school’s administration was not moved. The artist set up a functioning daycare in the gallery of her thesis exhibition which created a platform for public discussions of how budget cuts to public services in Britain were affecting small children and families. Many things came out of Francke’s functioning daycare installation. She connected with local nurseries and other parents. She broke boundaries between public (gallery/university space) and private (daycare, childhood, etc). She also realized that her fellow students without children were not concerned with her struggle, because they felt it didn’t apply to their lives—she felt invisible as the parent of a small child in an academic art context.

All of these discoveries led to her work with the Showroom, a gallery in London that works with the intersection of art, research, and participation. They invited Francke as part of Communal Knowledge, a series with artists partnering with local groups and organizations in the Showroom’s neighborhood—considered one of the poorest in Great Britain.

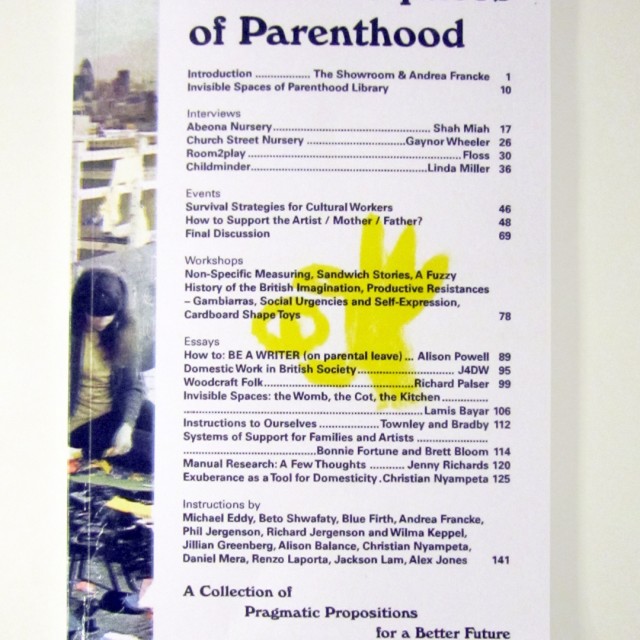

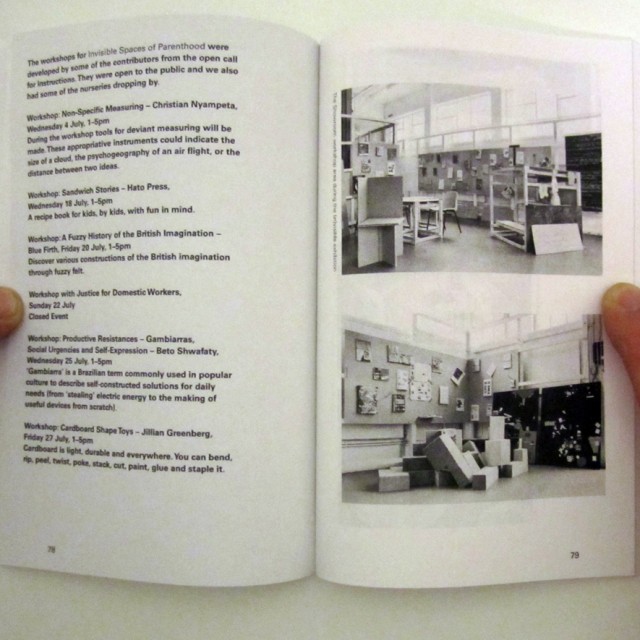

Francke put together Invisible Spaces of Parenthood: A collection of pragmatic propositions for a better future, an exhibition that expanded on her thesis show with events, workshops, interviews with childminders and other care workers, activist connections, and a publication.

As part of her research for the exhibition, Francke made the ISP Library which collected a diverse set of titles together like Mother Reader by Moyra Davey, in which mothers discuss with candor their experiences from joy to ambivalence, Tænke Bygge Bo, in which architect Gitte Juul works with 9-12 year olds on a model city, and Nomadic Furnitures 1 & 2, books about how to make furniture from cardboard on the fly, including a cardboard car seat.

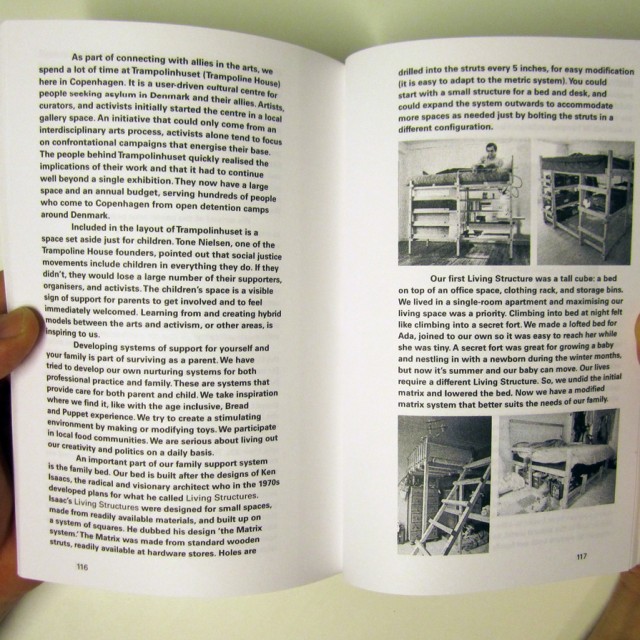

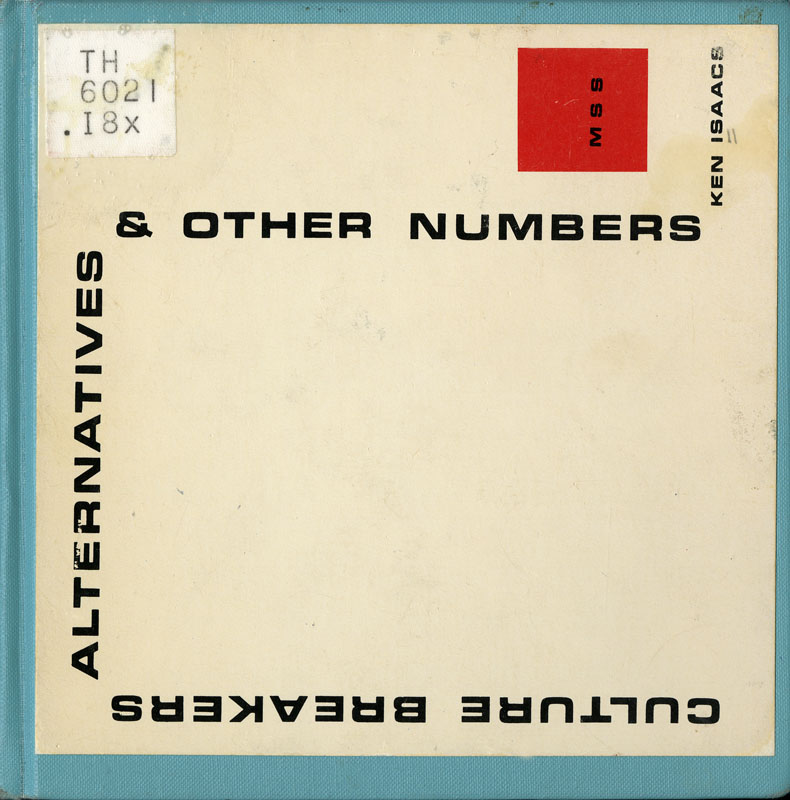

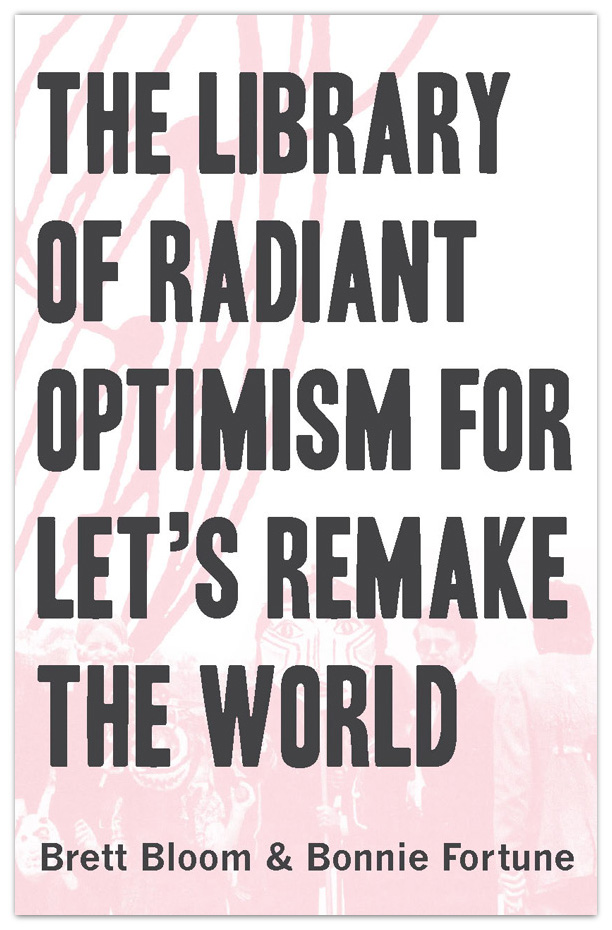

Incidentally, Francke pulled many titles from The Library of Radiant Optimism for Let’s Remake the World, that Brett and I started in 2006. Our library project collected books from the 1970s about sharing knowledge on how to build a different culture from home birthing to living systems for growing food. The ISP Library focuses on ‘education, utopic parenthood, and DIY’ culture. Both of our libraries were heavily inspired by the Whole Earth Catalog, a pre-Internet, analog, Google search engine in book form for the counterculture, as well as the work of Ken Isaacs, the radical architect who we have mentioned several times here on the MQ.

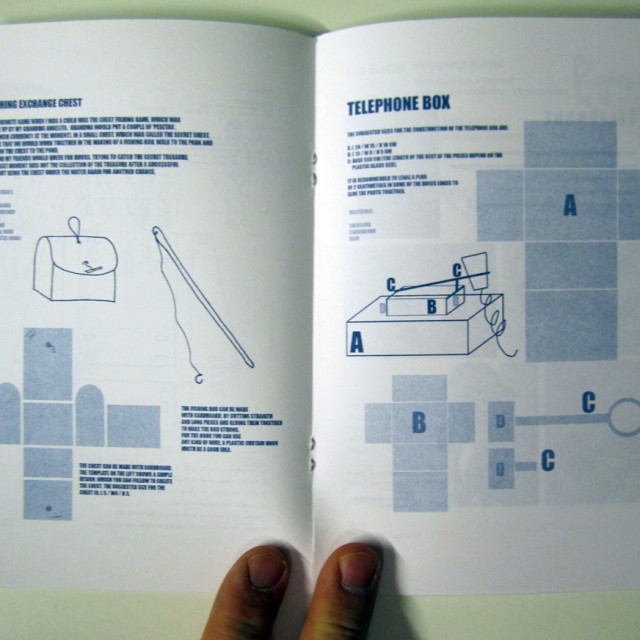

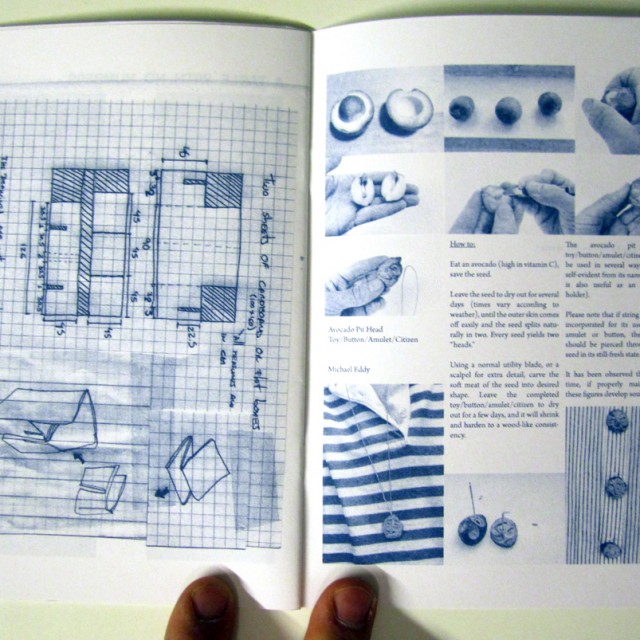

Francke created modular Isaacs-style frames as part of the exhibition design. Then to document the library, the exhibition, the discussions, and interviews, Francke put together a book with a design aesthetic that follows that of the Whole Earth Catalog, and even includes an insert devoted to DIY, low cost projects to build with children.

Invisible Spaces of Parenthood not only engages with arts and culture communities but involves the workers, users, and organizers of daycare centers in the Showroom neighborhood. Readers of the book begin to understand how early childhood shapes the foundations of larger society and what these communities that are often ignored, or rendered invisible, are actually providing.

One aspect of the book that I was particularly engaged with was the struggle of domestic care-workers who have to leave their own families to come to Great Britain to care for the children of others. In an essay titled “Domestic Work in British Society,” the Justice for Domestic Workers (J4DW) activist group details what it means, from the emotional pain to the economic need to the daily slights and larger injustices, to be a domestic work in the United Kingdom.

Brett and I contributed an essay to the publication that focuses on creating support systems for families and artists. We respond to Francke’s premise that parents and children are rendered invisible in contemporary public life by focusing on our experiences as artists and parents. We will post our essay in its entirety later in the week.

We will also be posting an interview with Francke in the next few days. Her interview will mark the start of a new series titled, Artist Parents.

We are very happy to have been included in this project which deftly melds personal experience, practical and theoretical research, community engagement, and activism–also tin can telephones, because yay!

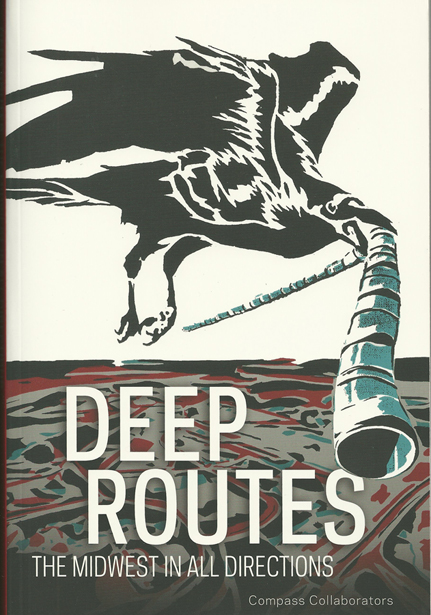

Radio Aktiv Sonic Deep Map (2013)

SUPERKILEN – Extreme Neoliberalism Copenhagen Style

Read Brett's essay about the park.

Download our guide:

This is our guide to how-to books from the counterculture of the 60s and 70s. Click to get the download page.

Categories

- Agriculture (11)

- Animal sounds (1)

- Artist parents (19)

- Arts and culture (106)

- Bees (3)

- Book reviews (14)

- Books (18)

- Critical essays (5)

- Daily Photo (5)

- Design (36)

- Dirt (11)

- Environmental activism (43)

- Exhibitions (24)

- Farms (11)

- Forest (7)

- Friday connect (15)

- Growing (42)

- Habitat (38)

- Homesteading (16)

- Interviews (15)

- Kitchen (14)

- Living structure (9)

- MISC (15)

- Mythological (2)

- Neighborhood (83)

- Ocean News (1)

- Our Art Work (21)

- Personal – Design/Art (3)

- Play (2)

- Playground (4)

- Projects (21)

- Public space (53)

- Resilience (13)

- Sea Side (2)

- Sojabønner (2)

- Tofu (8)

- Vermont correspondence (7)

- Water (3)

- Wednesday picture (31)

- Workshop (1)

Video interview:

Watch our interview of SeedBroadcast, a mobile project that is part seed library and part seed-saving-story-collecting machine-recording the stories of seed saving, farming, and food sovereignty work being done around the US.

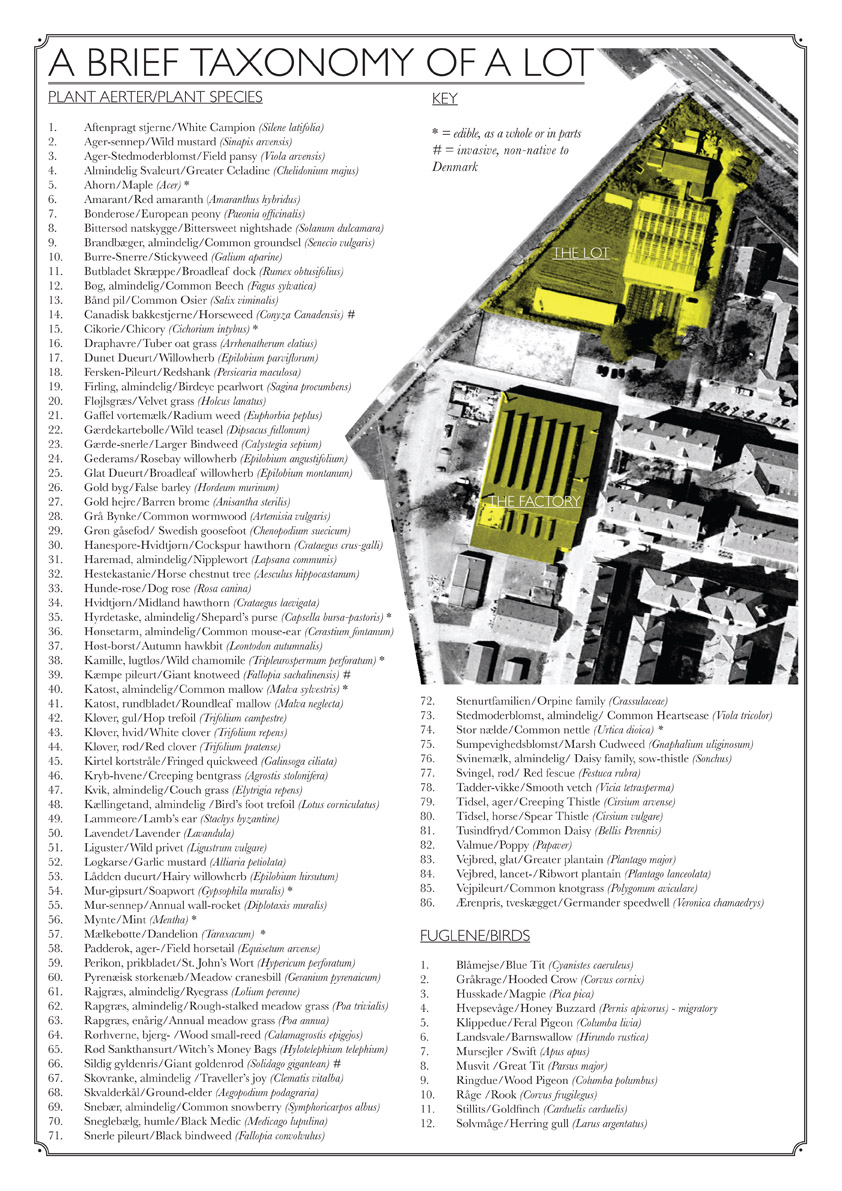

Download a poster Bonnie made about biodiversity in a vacant lot in the Amager borough of Copenhagen, in collaboration with biologist, Inger Kærgaard, ornithologist, Jørn Lennart Larsen and botanist, Camilla Sønderberg Brok: A BRIEF TAXONOMY OF A LOT

We made and installed a network of bat houses in Urbana, Illinois, to support the local and regional bat population, but also to begin a conversation about re-making the built environment.

READ MORE

BOOK REVIEW:

We write often about artists and art groups that work with putting ‘culture’ back in agriculture. Here is a new favorite: myvillages, a group of three women based in Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. Read more...

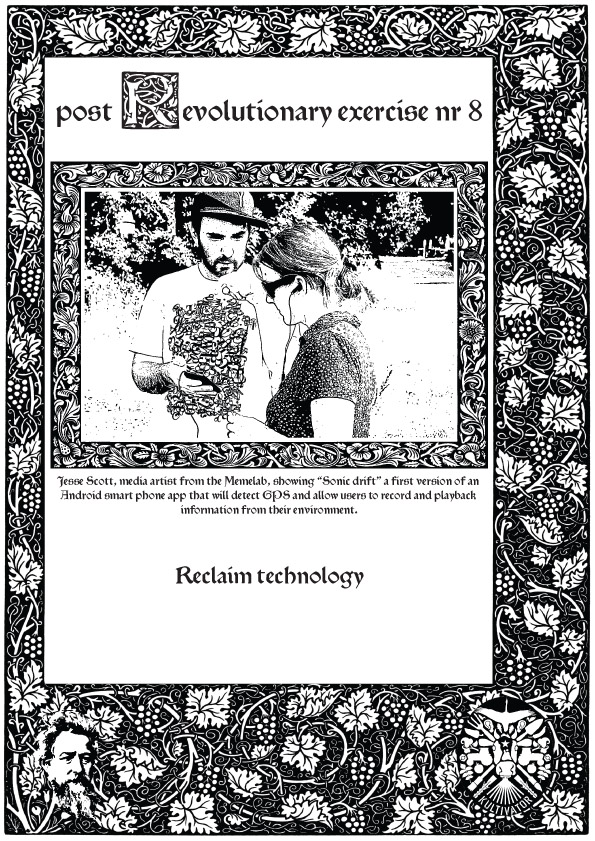

Post Revolutionary Exercises

We really admire the dedicated hard work of Kultivator who seeks to fuse agriculture and art in their work. Click this sentence to get a PDF of their poster collection called "Post Revolutionary Exercises."

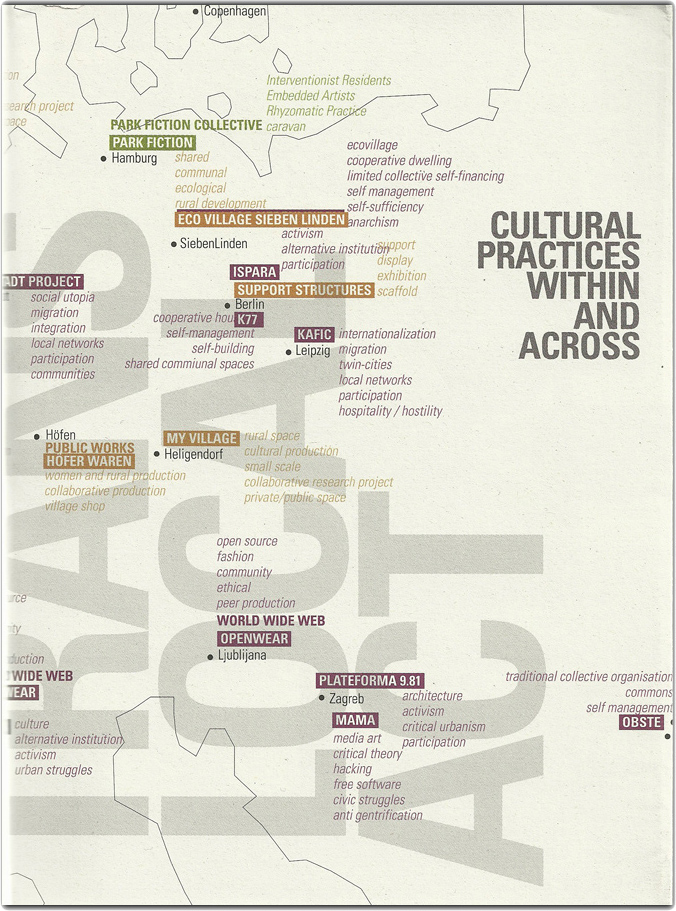

Cultural Practices Within And Across

This amazing book networks urban and rural resilience and sustainability projects around the world. Deeply inspiring projects in Romania, Paris, San Francisco, and elsewhere.

• Read our review of the book.

• Buy the book.

• Download the book.