Artist Parents: Andrea Francke

This post marks the first in a new series here at the MQ about Artist Parents and the ways in which they maintain a creative practice while balancing the labor of parenting. Each Artist Parent post will feature information about what the artist is working on + any comments that they have about life as a parent. This post also concludes our posts on Invisible Spaces of Parenthood: A Collection of Pragmatic Propositions for a Better Future, the exhibition and book organized by London based artist, Andrea Francke.

We recently talked to Andrea via email about her artistic practice and her parenting practice and are sharing the conversation in edited form here.

Andrea is Peruvian but grew up in Brazil. She moved to London along with her husband to complete a MA in Fine Arts. She had her son, Oscar, in London. She is currently involved with two long term art projects, The Piracy Project and Invisible Spaces of Parenthood. For Andrea, these projects are “platforms that spring from a very personal interest and expand to encompass research, a community of peers, events, workshops, and publishing,” among other things. Andrea tells us this about her work:

The Piracy Project is run as a collaboration with Eva Weinmayr under the umbrella of AND Publishing. We gathered a collection of pirated books through an open call and through research and we use them as a starting point to discuss issues around authorship, ownership, intellectual property, originality, cultural commons, etc. We make the collection available to the public as much as possible and we organize workshops and events.

Invisible Spaces of Parenthood (ISP) was born of my experience [of] becoming a mother. The sudden realization that there were an incredible number of structures–physical and social–that had been always around me but I never payed attention to. [ISP] functions as a platform to explore a subject from different perspectives. There is an essayist quality that I really enjoy when I’m working. I start by mapping the issues that I’m interested in, in this case: artistic labour/ domestic labour, the voice of the mother, DIY and utopic movements, radical pedagogy, the nursery in the community, the politics of childcare, etc. And then try to build small projects that allow me to develop or research those issues and to get in touch with communities or other individuals who are interested in them as well. There are some moments of chaos and messiness but it’s a really enjoyable process. Most of the collaborators of ISP where people that I met through the project itself.

Andrea says that her fluid, collaborative, and varied practice allows her to produce the kind of art world she is interested in participating in:

I have a love and hate relation with Art. I’m more and more interested in working outside the art system and connecting back to it just in a parasitical way. There are many manners or areas of working that can only be viable by calling them art so I’m interested in what I can get away with.

We went into more detail with Andrea about her work on ISP, because of the recent publication based on the exhibition of the same name. ISP began as Andrea’s thesis show and evolved into the exhibition which took place from 26 June-26 July 2012. She tells us a little about the inspiration for the exhibition:

Oscar used to go to the University of the Arts nursery while I was doing my MA. In the middle of the course, the UAL decided to close it and transform it into class space. There were about 60 parents using it– teachers, students and staff. We organized protests and impact studies, but nothing worked. While this was happening I tried to engage my classmates and the responses were usually that they didn’t have children so they didn’t care. I had never felt like this before. Suddenly, I was an other who had a very different existence and my two identities didn’t seem to integrate.

For the final show I built a temporary nursery in my space. I used the old 60’s and 70’s manuals my mum used to have around when I was growing up to build the furniture. We did very simple toys that the children could build upon and share. The idea was that this was an utopic nursery that we could use as a model if we had the chance to build the nursery again. Many of the parents and workers from the UAL nursery dropped by and adults could come in even if they were unaccompanied by children. It became a place where the two worlds could co-exist and have a dialogue. My favorite part was the three or four times where other young students will pass by while showing the parents around only to turn back and dismissively pronounce that it was, “Nothing, just a student doing something about a nursery because it was being closed or something like that.” Every time the mother will pull the student inside the space and start describing how she used childcare to go back to work, or how she had had to stay at home, and what all this had meant to her. Teachers would talk about the fact that the nursery was the result of internal campaigning to begin with and that it had an impressive effect on the proportion of women in staff.

The Showroom exhibition began with the idea to stage a temporary nursery, similar to the one from her thesis show, during the summer holidays, but after doing research in the neighborhood, she found that her pop-up nursery might prove to be a problem for the nurseries already struggling for funding. Starting with the subjects that had come up in the initial iteration of the project, such as “how the nurseries affected the community and how the cuts [Eds. The budget cuts to public services under David Cameron’s governance in England] were affecting them; why were the spaces of parenthood invisible; how did artistic labour relate to reproductive labour, different models of playing and learning,” she began working with others to develop what would become this summer’s exhibition.

Andrea conducted interviews with London nursery workers to develop an understanding of their everyday experiences, which are published in the ISP book. She says:

I think there is a really problematic issue in the way that knowledge is treated as an elite product (same with art). Is really important to me to find ways to connect to other types of knowledge that are constantly being produced but not really heard outside of their spheres. The nursery workers that I interviewed, for example, had really interesting perspectives and perceptions of their everyday practice that were invaluable to the project. I can say that I learned a lot more from the workshops, interviews and contributions in general that I feel I gave back. I don’t see my relation to the community as one that comes from above and improve or enrich their lives, I find those narratives really dangerous. Specially here in London were community art or social practices seem to be more and more used as a way to “deal” with social inadequacies or to promote a neo-liberal agenda. There is a big funding investment in these type of practices and I definitely feel conscious and uncomfortable about it.

The ISP project focused on expanding spheres of knowledge from the everyday experiences of nursery workers to the possibility of rebuilding society starting with homemade furniture.

Andrea was inspired by design manuals from 60s and 70s, such as Nomadic Furniture and How to Build Your Own Living Structures when developing the exhibition design. Andrea says,”There was something about the manuals that I used to build the original furniture that also intrigued me. I liked the practical sense that you could re-think and question everything by re-inventing the way you did even the smaller tasks in your life.”

During the course of the ISP exhibition, Andrea ran workshops along with others on topics from building a sandwich to the Justice for Domestic Workers activist group, who are trying to create laws that protect international domestic workers in the UK. For Andrea, some workshops were more successful than others depending on the dialogues that happened surrounding each workshop. The Justice for Domestic Workers was a more successful one:

We had a lovely experience with the Justice for Domestic Workers workshop. They came on a Saturday and we had a long discussion about their relation with childcare. They were all amazing woman with really powerful experiences. Many of them left their kids on their countries and came here because that was the only way they could give them a better future. They take care of the children of others and are very badly treated most of the time. The way visas and the justice system work enables a very perverse structure of oppression. They were so generous with us, sharing their stories and one of the rare free days they have, that I felt almost embarrassed that I didn’t had that much to offer. We spend the rest of the afternoon building things from the manuals. We published one text from them afterwards because the recording was too chaotic and emotional to transcribe. It was a great afternoon and they said they really enjoyed it.

Andrea’s experience working with communities that are not typically involved with an arts context, such as the nursery workers and the Justice for Domestic Workers group, prompted this reflection:

I guess, I’m mostly just grateful working with others. I try my best to give back as much as I can, but I’m aware it is never really enough. This discomfort comes from my lack of faith in the value art has just by being art. I hope publishing their text, publicizing their struggle as much as possible, and just honestly acknowledging that there maybe something lacking in my part of the relationship can suffice by now.

The ISP project is continuing beyond the exhibition stage. Already ISP can be found in book form and Andrea is currently developing a book project to make in collaboration with her son, Oscar’s school class. She says, ” I want to create a book with the children were they can actually be the authors of the content.” Oscar has taken part in two book projects in association with his mother this year. Which brings us to the other part of this post, how is Andrea’s art practice related to her parenting practice?

Andrea says that managing work time and child time is a constant negotiation.

I’m very lucky in that Oscar’s school has a great after school club and he really enjoys it. He stays until 5:00 at the school three days a week and those are my really productive days. I try my best not to work when he is around or work on things that can involve him. He loves to help me with building and sewing. He went to The Showroom while I was doing my residency and was very proud of helping building and painting. I’m very lucky in that I have some support from my family. I’m going to Peru next years for two week during holidays to do research on the Piracy Project and I’ll take him with me. My mum, aunts, cousins will all chip in to help me with childcare. I will have to slow the traveling down a bit I think until he is bigger. The school adds a lot of work and it has imposed a new structure to our lives.

She says that it has taken her a long time to get to the place where she is able to better manage her time to complete projects. Interestingly, Andrea says that she feels obligated to be productive whenever Oscar is not around, forgoing time to daydream and wander around town and focusing on making artwork.

Balancing childcare with her partner is also a negotiation depending on who has paid work and who doesn’t. Currently, her partner has a full time job so Andrea’s schedule as a professional artist, by default, has to maintain a certain flexibility to be able to take care of Oscar. Andrea does travel frequently for artist residencies and other artistic projects. The trips vary in length form a week to a month. She was in China for a month long residency last year. She says:

The month in China was great for [Alex and Oscar] and had a strong effect on the everyday life. They had a great time and had to find their own way of doing things. Alex first phrase on the airport was, ‘How can you do all of this? I never realized. I wouldn’t be able to keep it up.’

Andrea says about her experience with domestic life, ” It’s funny because Alex and I come from a different cultural setting where childcare is naturally concentrated on the mother so I’m always very conscious that if we stop thinking about it I will just take over.” Her advice for artist parents is that it is possible to be a parent and an artist because there are many other artist parents around. She says:

There is something about assuming you are a mother that is quite scary when you are an artist. Makes you feel really alone. I’ve heard so many times that to become a successful artist you have to give motherhood up that it was somehow internalized. When I met Anette Krauss and she introduce me to her daughter I was so happy I just wanted to hug her. I had so many questions. How was it? How have you done? I realized it was possible.

Finally, Andrea’s thoughts on being a parent now:

Another thing I’m quite interested is that I think we over complicate parenthood somehow this days. Children are treated as such precious beings that to raise them and caring for them has become a weird obsession. There are so many discussions about all the ways in which you are constantly damaging your children and how you should be doing everything in your power to be the best parent in the world to them. I think that is really destructive for everyone involved. It takes children out of society, and it attempts to erase any other identity you may have as a parent. When I decided to put Oscar in a nursery I was filled with guilt, and many people, even strangers felt that it was OK for them to tell me that I was doing something wrong, that it would damage him. He really enjoyed it. When I asked my mum about her experience being a working mother she said, ‘I missed you during the day but I loved my work’. That was it. She didn’t think twice about it. She didn’t even make an excuse of needing to work. I really long for that feeling of simplicity. Having children is part of life. It changes your life for ever, as many other things do. And then life goes on.

Radio Aktiv Sonic Deep Map (2013)

SUPERKILEN – Extreme Neoliberalism Copenhagen Style

Read Brett's essay about the park.

Download our guide:

This is our guide to how-to books from the counterculture of the 60s and 70s. Click to get the download page.

Categories

- Agriculture (11)

- Animal sounds (1)

- Artist parents (19)

- Arts and culture (106)

- Bees (3)

- Book reviews (14)

- Books (18)

- Critical essays (5)

- Daily Photo (5)

- Design (36)

- Dirt (11)

- Environmental activism (43)

- Exhibitions (24)

- Farms (11)

- Forest (7)

- Friday connect (15)

- Growing (42)

- Habitat (38)

- Homesteading (16)

- Interviews (15)

- Kitchen (14)

- Living structure (9)

- MISC (15)

- Mythological (2)

- Neighborhood (83)

- Ocean News (1)

- Our Art Work (21)

- Personal – Design/Art (3)

- Play (2)

- Playground (4)

- Projects (21)

- Public space (53)

- Resilience (13)

- Sea Side (2)

- Sojabønner (2)

- Tofu (8)

- Vermont correspondence (7)

- Water (3)

- Wednesday picture (31)

- Workshop (1)

Video interview:

Watch our interview of SeedBroadcast, a mobile project that is part seed library and part seed-saving-story-collecting machine-recording the stories of seed saving, farming, and food sovereignty work being done around the US.

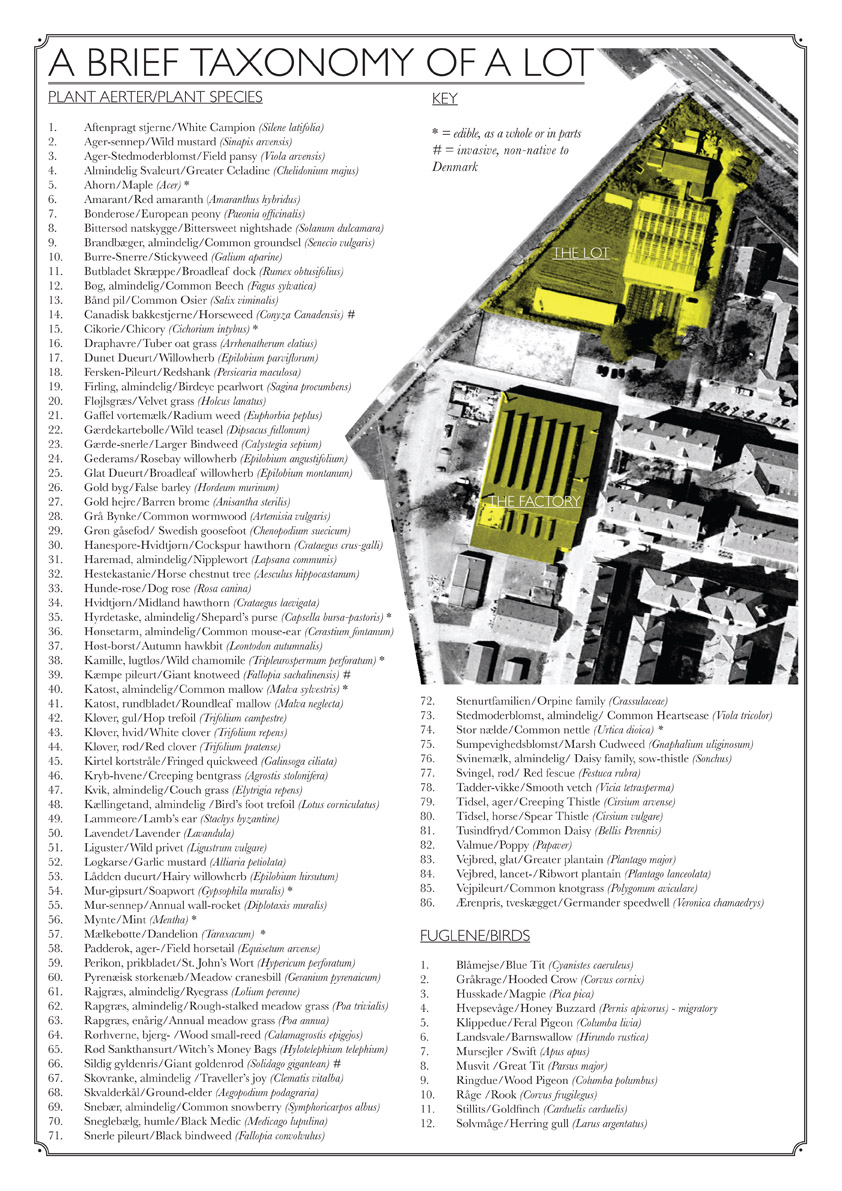

Download a poster Bonnie made about biodiversity in a vacant lot in the Amager borough of Copenhagen, in collaboration with biologist, Inger Kærgaard, ornithologist, Jørn Lennart Larsen and botanist, Camilla Sønderberg Brok: A BRIEF TAXONOMY OF A LOT

We made and installed a network of bat houses in Urbana, Illinois, to support the local and regional bat population, but also to begin a conversation about re-making the built environment.

READ MORE

BOOK REVIEW:

We write often about artists and art groups that work with putting ‘culture’ back in agriculture. Here is a new favorite: myvillages, a group of three women based in Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. Read more...

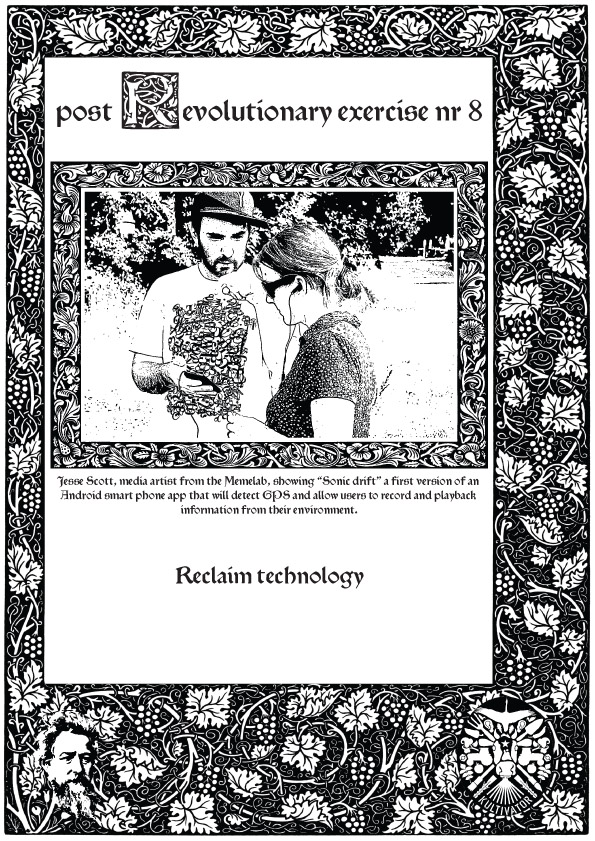

Post Revolutionary Exercises

We really admire the dedicated hard work of Kultivator who seeks to fuse agriculture and art in their work. Click this sentence to get a PDF of their poster collection called "Post Revolutionary Exercises."

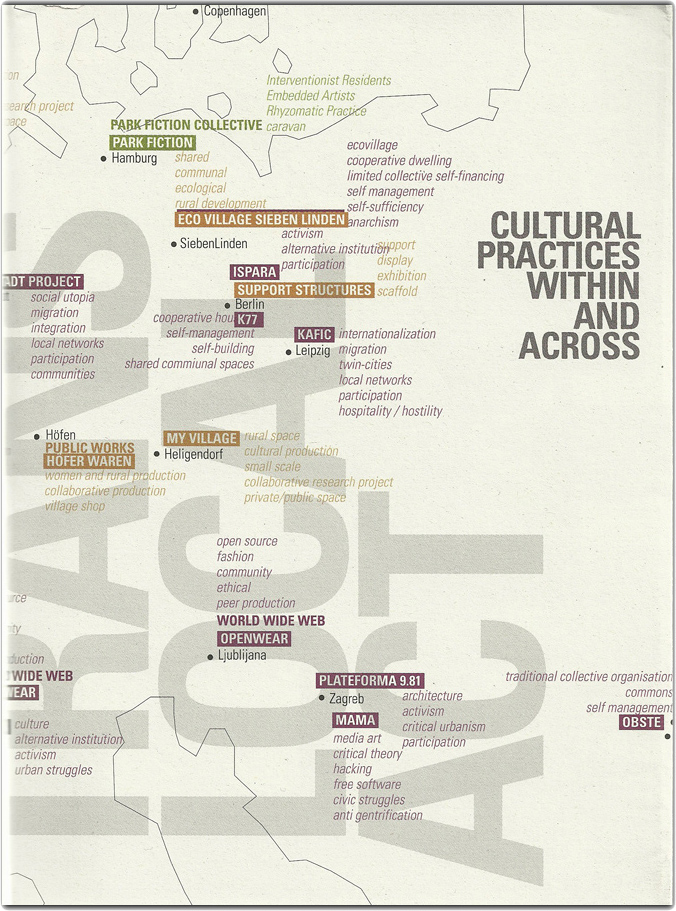

Cultural Practices Within And Across

This amazing book networks urban and rural resilience and sustainability projects around the world. Deeply inspiring projects in Romania, Paris, San Francisco, and elsewhere.

• Read our review of the book.

• Buy the book.

• Download the book.