Systems of Support for Families and Artists

The following is our full essay from the Invisible Spaces of Parenthood: A collection of pragmatic propositions for a better future book which we posted about earlier this week.

Systems of Support for Families and Artists

By Bonnie Fortune and Brett Bloom

We are both artists. Our daughter, Ada, was born in December of 2011. Only recently, have we figured out a system that allows us each to have time alone to think about our creative work.

A creative practice demands uninterrupted time to think. A parent’s attention is constantly shifting between what the baby needs–right now!–and planning for the future, the immediate, as well as the long term. We strive to create an embodied art practice that makes no distinction between our daily and “professional” lives. We do not want to pretend that child rearing is not something that is a huge part of who we are as artists and people. We are looking for ways to have creative balance in family and in work.

Our experience so far is of a “professional” art world that is biased against people with children. In talking with other artist parents, we share stories about the difficulties of being creative and a parent. For example, we know a single mother who is an artist. She says her desire to do both–raise children and be an artist–is often met with suspicion, derision, or confusion. In some cases, she has been told that she is a less serious artist because of being a mother. In other situations, there is a skewed labor division between the two caregivers, with one parent taking on the larger share of domestic tasks, while the other parent works at his or her art career.

We recently took our daughter with us to a conference on collective art practice for artists who work in groups. We want a contiguous relationship between our art making and our lives so it was an obvious thing for us to bring Ada along. Many of the conference attendees were also politically active and involved in socially engaged art practices. The conference was organized with the idea of building stronger networks of support for artists who work in groups and collectives. Though this mode of art making has gained significant legitimacy in the recent era, it is still perceived as an exception to the rule rather than the norm.

We arrived at the conference prepared to engage in solidarity work for forming support systems within the art world along with our daughter. At first, Ada’s presence was met with discomfort and mild annoyance. Though we spent a large portion of our time on discussions to make sure that everyone was on the same page about supporting people of color, queer people, and women, and many attendees were parents of older children—the presence of a young child was not met with much solidarity.

During the gathering we took a trip to visit the Bread & Puppet Theatre, an organization that for over 40 years has been making political puppet performances on issues of social justice, in Vermont and around the world. We attended a multi-hour puppet pageant–a magical experience set against the backdrop of rolling fields, forest, and the Green Mountains. Over 500 people attended and they ranged in age from a few months old to those well into their 80s. There seemed to be an understanding amongst the attendees of the gathering that there would be a multitude of voices both young and old in the audience. The experience was expansive, inclusive, and engaged in a way that our small gathering of politically left art groups was not, even though we ostensibly shared politics with the Bread and Puppet performers. When we returned to the conference, our next group discussion was way more relaxed and accepting of Ada’s presence.

As part of connecting with allies in the arts, we spend a lot of time at Trampolinhuset [Trampoline House] here in Copenhagen. It is a user-driven cultural center for people seeking asylum in Denmark and their allies. Artists, curators, and activists intitially started the center in a local gallery space. An initiative that could only come from an interdisciplinary arts process, activists alone tend to focus on confrontational campaigns that energize their base. The people behind Trampolinhuset quickly realized the implications of their work and that it had to continue well beyond a single exhibition. They now have a large space and an annual budget, serving hundreds of people who come to Copenhagen from open detention camps around Denmark.

Included in the layout of Trampolinhuset is a space set aside just for children. Tone Nielsen, one of the Trampoline House founders, pointed out that social justice movements include children in everything they do. If they didn’t, they would lose a large number of their supporters, organizers, and activists. The children’s space is a visible sign of support for parents to get involved and to feel immediately welcomed. Learning from and creating hybrid models between the arts and activism, or other areas, is inspiring to us.

Developing systems of support for yourself and your family is part of surviving as a parent. We have tried to develop our own nurturing systems for both professional practice and family. These are systems that provide care for both parent and child. We take inspiration where we find it, like with the age inclusive, Bread and Puppet experience. We try to create a stimulating environment by making or modifying toys. We participate in local food communities. We are serious about living out our creativity and politics on a daily basis.

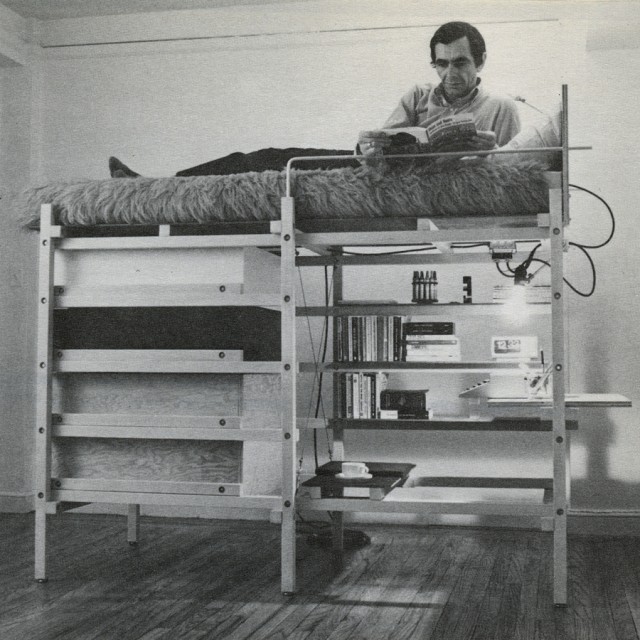

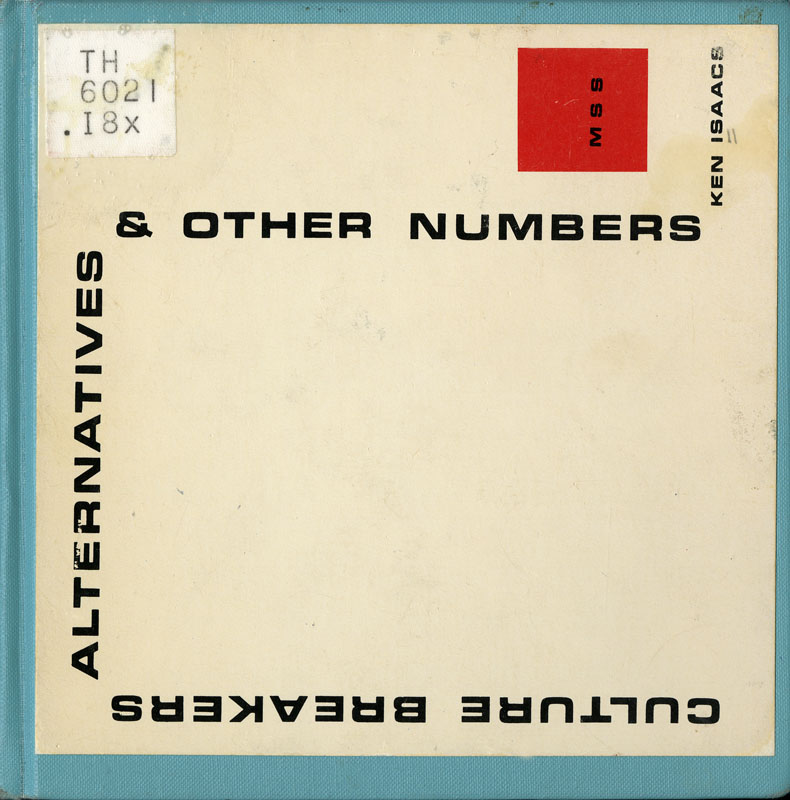

An important part of our family support system is the family bed. Our bed is built after the designs of Ken Isaacs, the radical and visionary architect who in the 1970s developed plans for what he called Living Structures. Isaac’s Living Structures were designed for small spaces, made from readily available materials, and built up on a system of squares. He dubbed his design ‘the Matrix system.’ The Matrix was made from standard wooden struts, readily available at hardware stores. Holes are drilled into the struts every 5 inches, for easy modification (it is easy to adapt to the metric system). You could start with a small structure for a bed and desk, and could expand the system outwards to accommodate more spaces as needed just by bolting the struts in a different configuration.

Our first Living Structure was a tall cube: a bed on top of an office space, clothing rack, and storage bins. We lived in a single-room apartment and maximizing our living space was a priority. Climbing into bed at night felt like climbing into a secret fort. We made a lofted bed for Ada, joined to our own so it was easy to reach her while she was tiny. A secret fort was great for growing a baby and nestling in with a newborn during the winter months, but now it’s summer and our baby can move. Our lives require a different Living Structure. So, we undid the initial matrix and lowered the bed. Now we have a modified matrix system that better suits the needs of our family.

We brought Ada’s bed down to the floor in the tradition of Maria Montesorri, whose educational model encourages free movement and self-determination in children. The Montesorri-Living Structure floor bed (we are sure it is the first of its kind) allows Ada to move in and out of her own volition. Her bed is next to our modified matrix bed-now much lower, but still providing storage underneath.

As Ada grows, we will build other structures to accommodate the needs and desires of our family. Maybe a bed that more resembles our own–raised off the floor with storage and hiding places beneath, or a bookshelf fort system, with a built in light, for tucking in and reading. We will build towers to climb with platforms for playing and imagining many worlds. We will eventually help her to build her own structures as she gains the motor and conceptual skills necessary to accomplish this. We will teach her how to prepare the wood and to use a drill. We will take her to source wood from dumpsters and piles outside of apartment buildings, construction salvage warehouses, or make trips to local hardware stores.

The two of us pull a tremendous amount of strength and comfort from having the skills to create the systems that make the daily world we inhabit more our own and less that of the dominant culture. We look to many sources from books to other artists, to friends and family and to the natural world, to develop systems of support to nurture both our family and our art practice. We hope that modelling resourceful behavior will help to prepare Ada, and give her the confidence to see herself as more in control of her world. Our goal is to integrate Ada, and children in general into the things we do as artists. This feels like a more honest way to develop our work, rather than focusing on the machinations of surrounding professionalism.

Radio Aktiv Sonic Deep Map (2013)

SUPERKILEN – Extreme Neoliberalism Copenhagen Style

Read Brett's essay about the park.

Download our guide:

This is our guide to how-to books from the counterculture of the 60s and 70s. Click to get the download page.

Categories

- Agriculture (11)

- Animal sounds (1)

- Artist parents (19)

- Arts and culture (106)

- Bees (3)

- Book reviews (14)

- Books (18)

- Critical essays (5)

- Daily Photo (5)

- Design (36)

- Dirt (11)

- Environmental activism (43)

- Exhibitions (24)

- Farms (11)

- Forest (7)

- Friday connect (15)

- Growing (42)

- Habitat (38)

- Homesteading (16)

- Interviews (15)

- Kitchen (14)

- Living structure (9)

- MISC (15)

- Mythological (2)

- Neighborhood (83)

- Ocean News (1)

- Our Art Work (21)

- Personal – Design/Art (3)

- Play (2)

- Playground (4)

- Projects (21)

- Public space (53)

- Resilience (13)

- Sea Side (2)

- Sojabønner (2)

- Tofu (8)

- Vermont correspondence (7)

- Water (3)

- Wednesday picture (31)

- Workshop (1)

Video interview:

Watch our interview of SeedBroadcast, a mobile project that is part seed library and part seed-saving-story-collecting machine-recording the stories of seed saving, farming, and food sovereignty work being done around the US.

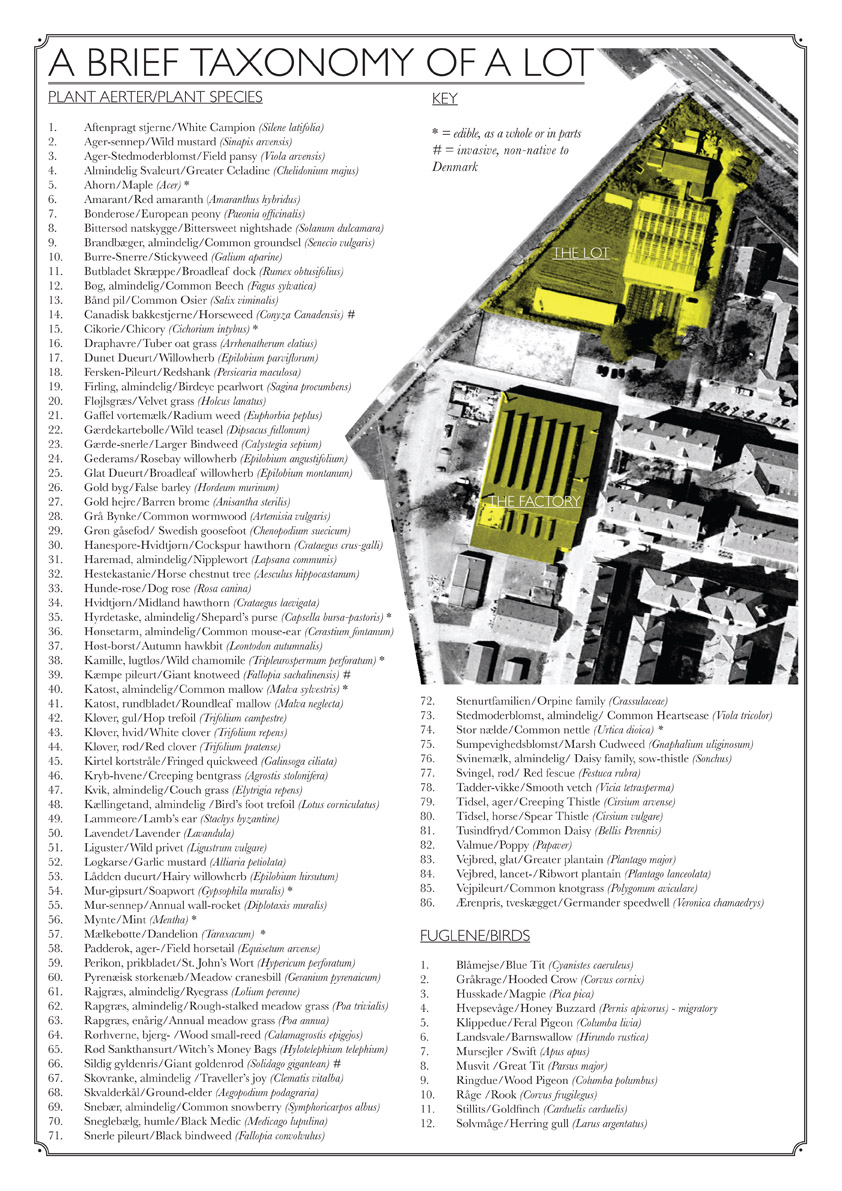

Download a poster Bonnie made about biodiversity in a vacant lot in the Amager borough of Copenhagen, in collaboration with biologist, Inger Kærgaard, ornithologist, Jørn Lennart Larsen and botanist, Camilla Sønderberg Brok: A BRIEF TAXONOMY OF A LOT

We made and installed a network of bat houses in Urbana, Illinois, to support the local and regional bat population, but also to begin a conversation about re-making the built environment.

READ MORE

BOOK REVIEW:

We write often about artists and art groups that work with putting ‘culture’ back in agriculture. Here is a new favorite: myvillages, a group of three women based in Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. Read more...

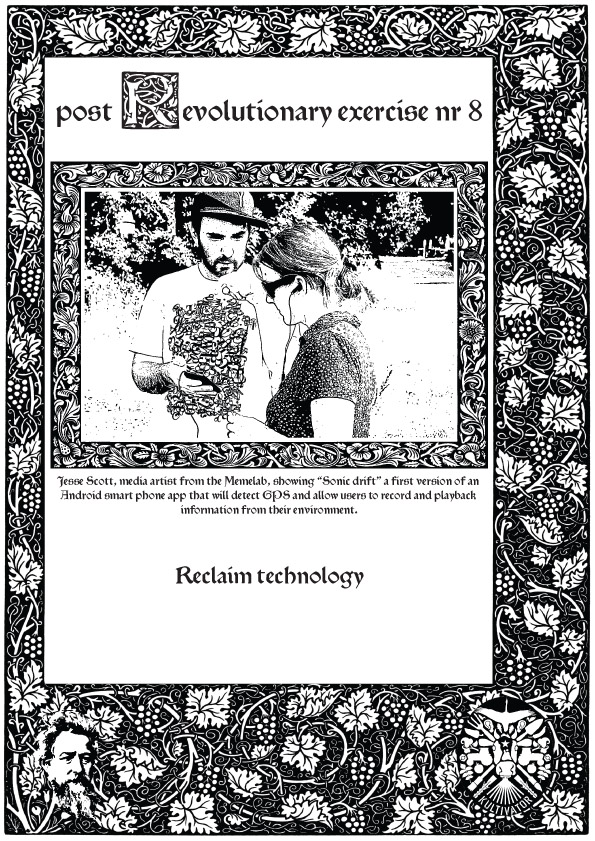

Post Revolutionary Exercises

We really admire the dedicated hard work of Kultivator who seeks to fuse agriculture and art in their work. Click this sentence to get a PDF of their poster collection called "Post Revolutionary Exercises."

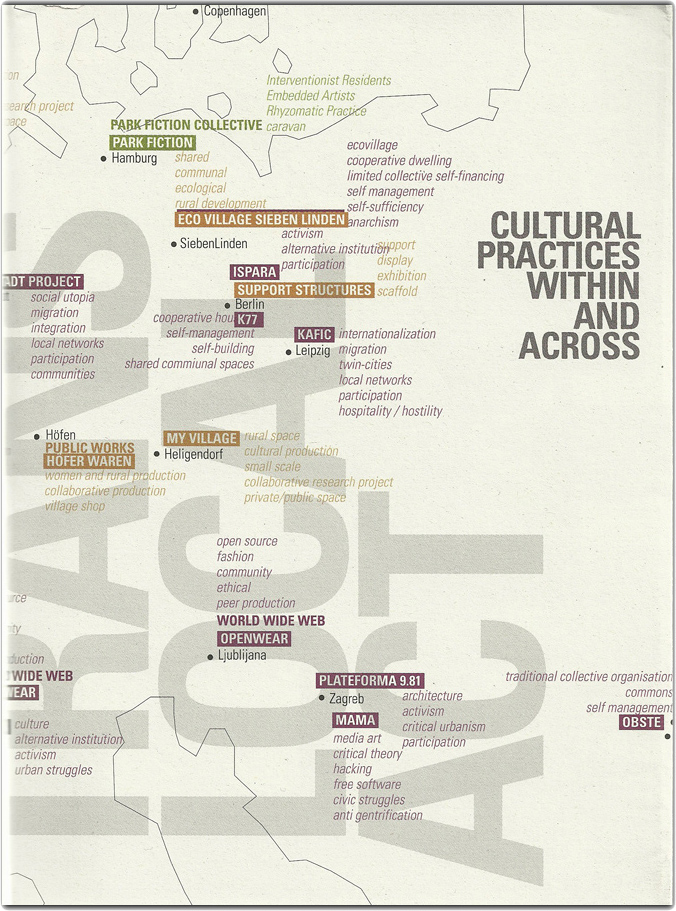

Cultural Practices Within And Across

This amazing book networks urban and rural resilience and sustainability projects around the world. Deeply inspiring projects in Romania, Paris, San Francisco, and elsewhere.

• Read our review of the book.

• Buy the book.

• Download the book.